My internship at UNESCO brought me face to face with many colourful characters and people of many nationalities and backgrounds, some not unlike my own. But out of all the people I thought I’d meet during my stay, Forrest Whitaker was not one of them.

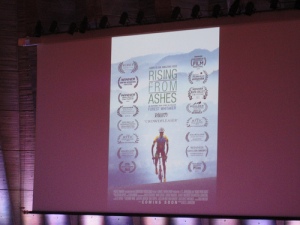

The US actor brought Africa to the screen as Idi Amin in The Last King of Scotland. This time, he brought Rwanda back to the limelight with an advanced screening of his documentary Rising from the Ashes. As a UNESCO Goodwill Ambassador, Whitaker allowed UNESCO staff, interns and visitors the chance to see an advance screening of the film, which he narrated and produced, before it hits French cinemas.

Set in Rwanda and spanning three continents, the movie tells the story of the first Rwandan national cycling team and its rise to fame under the guidance of Jonathan “Jacques” Boyer, the first American to compete in the Tour de France. Composed of genocide survivors, the men form an indestructible companionship as they compete in Rwanda, South Africa, the United States and finally in London for the 2012 Olympic Games. Boyer himself appeared alongside Whitaker on stage to present the film to the audience.

The film takes you from tears to laughter and back again as the stories of Boyer and the cyclists are revealed. The losses and misfortunes of the main characters will bring tears to your eyes while their triumphs will brighten your mood just as quickly. Most strikingly, it is an example of how the love of sport and a spirit of sportsmanship can be powerful enough to break down all the self-imposed barriers that we build up based on prejudices, resentment, apathy and cynicism. It tells about how the scars left behind by violence and hatred need not bleed forever. As a UN agency specialised in fostering cultural and educational cooperation in the aim of sustaining peace, Rising from the Ashes gives a concrete example of how UNESCO’s mission may be possible.

For more information on the film, click here